But first, a quick note from Hailo:

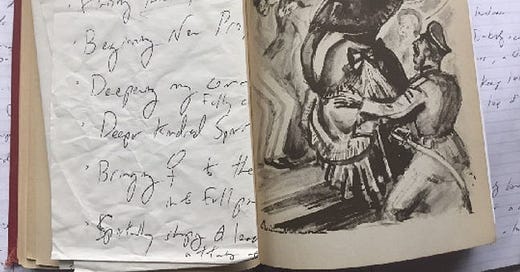

We're doing a ~drop~ but I'd rather call it a ~debut~. A little softer, right? Rolls off the tongue. Think of it as a little debutante ball for something like merch, if you can call it that. It's a very small, very bespoke collection of thrifted clothing and curated used books. Each book will come with my own reflectio…