I want to know what Hella’s room looks like. Is it small and caving like Giovanni’s? Forgettable and impersonal like David’s? I have a feeling that Hella’s room, like mine, is entirely in her head. Only a woman’s own mind can provide the kind of freedom Hella searched for because, after all, a woman’s place is in the private sphere, isn’t it?

I began reading Baldwin’s novel while in Paris but did not get too into it until after I returned home. It felt too real to read it there; walking through the streets and neighborhoods he names. Giovanni’s Room consumed me in a way that fiction hasn’t in a long time. In the way it used to when I was a child.

As I was about twenty pages from the end, someone on the subway approached me to tell me how much they love Giovanni’s room; “It makes me sad, but I love it.” They were tall and feminine in the way high fashion models are, with harsh masculine features and a fierce resting face. I had noticed them on the platform. I knew that they noticed me too, but I was too invested in finishing the novel to do anything about the slight tension between us. As they got off the train, I named them “Hella on the subway” in my head, and I dove back into the tragedy.

I finished the book standing outside The Natural History Museum waiting for the express bus. The sun had already set and the streets were quite empty. While I leaned against a ticketing machine for the M79, two drunk men leaning on each other’s arms crossed the street toward me. The one in the tight jeans and mildly transparent black button up saw me and screamed, in an aggressive, raspy voice, “HEY!” Naturally, I glanced at them to assess my danger and I quickly realized he was, whether he knew it or not, a gay man. His friend pulled him away and toward the train station, almost embarrassed, but not enough to offer an apology to me like many apologetic men would in these kinds of situations.

Here this man was, yelling at me, a perhaps visibly lesbian young woman (I was wearing a pinstripe vest with nothing underneath and knee length jorts) as if I was Giovanni himself and he was David. Or perhaps he was Jacques, or even Guillame. There was something palpable shared between us, a violent envy or confusion.

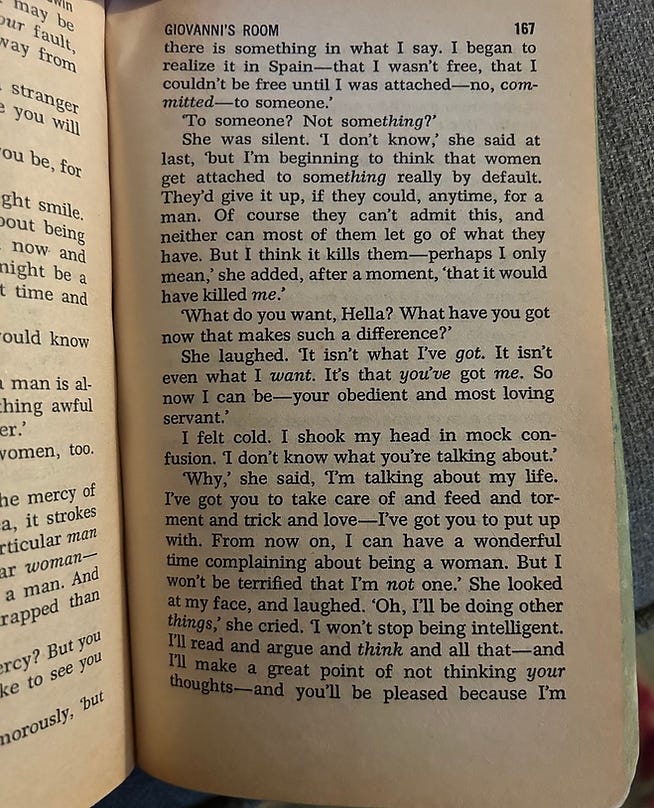

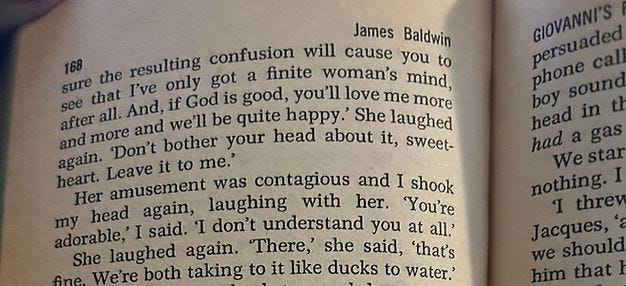

While Hella was in Spain and David was falling in love with Giovanni, I longed for her to write me letters about her independent adventures abroad. David had the privilege of sharing emotionally complex feelings with another, and I prayed Hella had the same; that she had finally found someone who understood her in the ways she needed to be. But instead she returned to Paris and she agreed to marry David out of a “humiliating necessity.”

To be a woman committed to a gay man is no womanhood at all. So I wonder – as I suppose I always have – whether to be a lesbian is any womanhood at all. Hella knows that a woman of her time can only lead a life of her own while in the societal sanctuary of heterosexual marriage. David is, of course, terrified of this, because he is paralyzed at the thought of leading his own life, and is just as terrified to be a gay man married to a woman, forced into leading a life that is not his.

Curiously, this dilemma made me think of U-Haul lesbians. Legalized monogamy has always been a perpetrator of heterosexism and continues to be society’s most romantic trap. The legend of U-Haul lesbianism is responds directly to this complex need for commitment by centering the publicly private sphere of a relationship that manifests in a shared living space

When David told people, especially Giovanni, that Hella was in Spain to figure out if she wants to marry him, it was received with an elitist distaste. Well if you love her, why would you allow her that time away? What could she possibly need to figure out?

David was quick to move in with Giovanni into his room despite resenting it so much. It is a classic gay love story, but it is of course also a consequence of their low-income circumstances, and maybe that is enough of an excuse in the eyes of the heterosexual public and Spanish Hella.

I am persuaded to believe that lesbians move in together quickly because it seems a fair compromise to make when existing between the fear of leading your own life as a lesbian-sans-womanhood and a woman-sans-freedom. A woman gets her freedom by marriage, and a lesbian gets her freedom by playing pretend in a straight world.

Here is David, a Black gay man in love with an white gay man but engaged to Hella, a white woman, and no one, not even the white folk, are winning this complex, life-long internal debate of racial, sexual, and/or gendered freedom. So what, then, of the Black lesbian woman?

A few nights ago I was having dinner with a dear friend. An older man and his tiny puppy passed our table. Leash-less, she followed behind him like a duckling to its mother. He paused so we could pet Miss Dumpling and he could inquire about our lives.

Is this a first date or something?

No, we are best friends.

How long?

Nine years.

You know you’re going to end up together, right?

We looked at each other, hiding our giggles, as we denied his premonition. We did not disclose that we were both gay and thus his hope for our love story is far from likely, but we continued to assure him we were good, and only, friends.

The man asked me if I told my friend about my boy troubles, and I said I did. He asked me if my friend told me about his girl troubles. I said yes. He then reiterated,

Yeah, you’re going to fall in love.

Had we disclosed our sexualities to this man I doubt it would have endangered us any more than we already were – being the subject of a sixty-something year old man’s romantic fantasies – but we both chose to keep this secret to ourselves. When he finally left we gawked at the irony of the situation; we had, in fact, spent the dinner thus far discussing our boy and girl troubles, just not in the straight way the man had hoped.

I enjoy allowing strangers to indulge in their assumptions about me. I am not one to correct someone who thinks I’m straight, or a bitch, or a tween, or anything else. Their perception of me is intriguing, no matter how wrong it is. I like to live in the fantasy of their mind, even if just for a moment. But this fantasy was particularly compelling, because it forced me to consider the ‘what ifs’ of this parallel reality. What if we were both straight and we were secretly in love with each other? What if this man had forced us to confront our feelings for each other? How simple life would be. Our future would be set, our feelings confirmed, our genders and sexualities realized. There would be nothing left to do but live.

The reality is that my friend is a Black gay man having love affairs with the modern Giovannis of the world, and I am a Black lesbian woman having love affairs with the queer Hellas of the world. The challenge is that the characterization and arc of the queer Hellas are not written out for me, or for themselves. I am a queer Black Hella myself, fighting with the woman question and the love question and the race question. I don’t have the luxury of novella predictability or the promise of liberation-via-marriage. Perhaps I am perpetually in Spain, or Paris, or New York, traveling to ‘figure things out,’ waiting for a letter from a lover or to feel something strong enough I’m compelled to write one myself. Will I be proposed to or will I have to do the proposing? Does my capacity for freedom change depending on which one I choose? Maybe I will find myself a heterosexist masc to move in with and we can have a big lesbian wedding. Maybe maybe maybe…we are all just trying to get free, aren’t we?

Hello! Really enjoyed your post, I love Giovanni’s room. One thing that stuck out to me is that you said that David is a black gay man. I recall David being described as a blond American, which I’m assuming means that he’s white. I remember my first question while reading this book being, “why did Baldwin write a gay white man?” I was 14, and now I’m 21, and I still ask myself that. I feel like it’d be interesting to analyze.