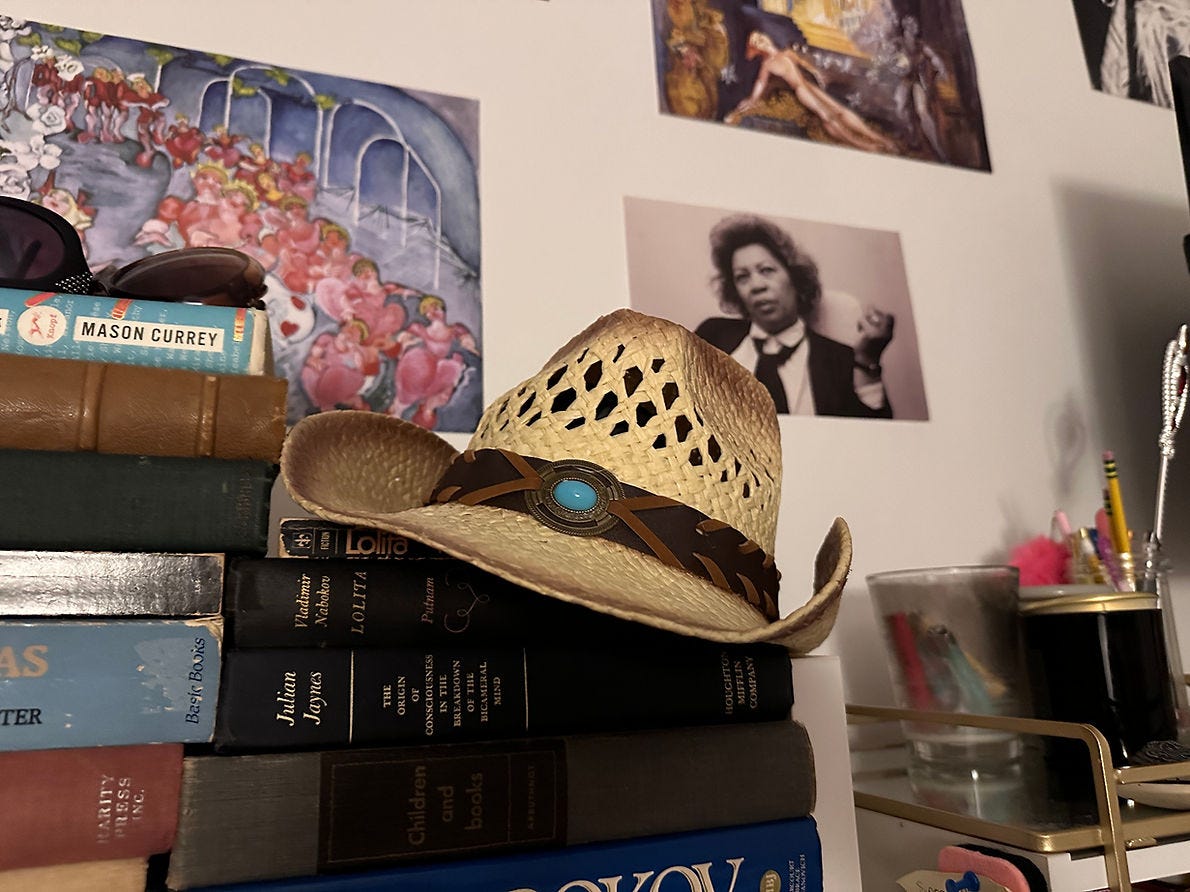

They didn’t know what to call us before. Descendants of Artemis; some kind of moon fable brought to life with our nimble hands and wild hair. Keepers of the ranch. Almost cowboys. It was the “almost” that made us dangerous – the space between what we could do as women and what they thought only they could do as men was too small to see us as other. The …

© 2025 Hailey Colborn

Substack is the home for great culture